Reading Time: 6 minutesYesterday morning as I prepared for work, I heard someone speak about the February 26 shooting of Trayvon Martin stating that he should have stayed with his father on that fateful night. Last week, in the first public interview of Martin’s parents, on The Today Show, one of Matt Lauer’s first questions to Trayvon’s mother and father was if there was any reason why Trayvon might have been agitated that night? The lawyer and friends of George Zimmerman have come forward to emphatically state that he was in a fight for his life, having emerged from the scuffle with a broken nose, scrapes, and grass stains on his clothes. They also state that he is not racist and has cried for days over the incident. In the released 911 calls, in George Zimmerman’s own words, he describes the boy as a suspicious person who keeps looking around and into windows. These thoughts and statements are all parts of the conversation as it continues to play out in the media each day. There are, I believe, key considerations missing from this conversation.

Stand Your Ground

The 2011 Stand Your Ground statute, Chapter 776 outlines justifiable use of force on the “presumption of fear of death or great bodily harm.” One question missing from the current conversation is, wouldn’t Trayvon Martin have the right and responsibility to stand his own ground as well? In all of the conversations I have not heard enough emphasis of the degree of the fright and alarm that Trayvon experienced by being followed by an adult man. In Trayvon’s case, it’s not hard for me to imagine that he was aware of his surroundings. In the clip of recorded conversation between Trayvon and his girlfriend, we hear her tell him to run. Should Trayvon have run home that night to avoid a confrontation? From an adult perspective certainly, he would likely be here today to share his own point of view if he had.

However, would it have been wrong for him to turn and face his follower? Certainly not. Who was this man who continued to follow him through the complex as he made his way from the 7-11 to his father’s townhome with his candy and tea? What had Trayvon done to be considered suspicious?

In my own imagination, I can easily see Trayvon, feeling relatively safe in his own neighborhood. He may have been tired of being treated as a suspect first, and 17-year old boy second and not wanting to be subjected to that behavior from others anymore, and so instead of running he turned and stood his ground.

Or, I can also see him as a somewhat cocky young man who, knowing that he was being followed, figured that he could handle the man on his own and turned to face him, thinking if it came to a fight, he would easily win. I can also see that as a young African American man, to run can be considered to be a coward, and with the mixture of the two scenarios, Trayvon turned to stand his ground.

We don’t yet, and might never, know exactly how Trayvon and George Zimmerman came to be in a struggle on the sidewalk that night, but I can imagine that Trayvon felt as threatened and in defense of his own life as George Zimmerman is reported to have felt, with the exception of the fact that Trayvon only had his fists to defend himself while George Zimmerman had a loaded gun.

History

Secondly, in all of this, history is curiously absent. It was not even 70 years ago (the 1950s and early 1960s) when lynching occurred with some regularity in the south. In the intervening years, where these incidents have widely been condemned and more people have been brought to justice for their participation, we continue to hear of incidents where Black men are dragged, tortured, and killed. In fact in the wake of this case, a recent NPR Morning Edition show featured writer Donna Britt regarding “the talk” she’s had with her two sons. The fact of the matter is I too have had similar discussions with my own 15-year-old multiethnic son. “The Talk” concerns how the world perceives them and their own responsibility to be aware of the perception, no matter how real or imagined, and to be prepared for the reaction they may likely receive at times.

I imagine that Trayvon’s parents had similar discussions with him regarding the dangers of the police and his interactions with White people in general that could lead to tragic consequences. Today a young Black man can’t be picked up simply for failing to yield the sidewalk to a White person, or for being “fresh” or overly friendly towards White women; however, it seems, if someone feels threatened, especially in states with Stand Your Ground statutes like Florida, there continues to be legal justification for killing young Black males.

Walking While Black

Thirdly, part of the conversation that remains largely absent is that I still have not heard of just cause for George Zimmerman to have followed Trayvon in the first place. Yes, there had been a few robberies in the area recently. Yes, according to reports, it is suspected that those crimes were committed by Black men. However, does that mean that every Black male is suspect?

It appears Trayvon became suspicious to George Zimmerman for “walking while Black.” He was a young Black man, unfamiliar to Zimmerman, walking at night with a hoody on. Our society perpetuates the notion of Black men as dangerous and criminal. People respond with fear and suspicion when we see Black males, particularly at night.

The continued perpetuation of fear of Black men every day in the media, in entertainment, and in our own imaginations, results in someone like George Zimmerman seeing Trayvon and easily justifying the ensuing actions in his own mind. Zimmerman, like all of us, consistently sees the message that Black men are dangerous, whether they are 12 or 35. He saw Trayvon and said to himself, this shadowy figure is up to no good.

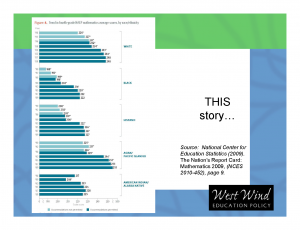

What’s more, this doesn’t simply happen in our neighborhoods or on the streets…this also happens in our classrooms and schools. We can examine the recent reports regarding disproportionate suspensions and actions of discipline in schools where Black males especially, but Latino males as well, are disproportionately suspended in schools[1]. Here we see school officials disciplining Black boys, in particular, for like-transgressions, often with the intent of “sending a message” as if Black boys are somehow in need of extreme measures to learn the same lessons about behavior, rules, and right and wrong as other kids. Rather it is the imagined consequence that “lenience” (which I consider to be more proportionate responses) does in light of the exaggerated notion of Black males as dangerous and criminal that underlies such decisions regarding appropriate discipline.

Underlying Beliefs

I’m troubled by a seemingly double standard. In our media and popular entertainment, we see the image of White males taking charge. On more than one occasion, I’ve seen stories of Iraq and Afghanistan vets, in particular, hailed for their quick thinking and response to threatening situations. In their cases, they emerge not only unscathed, but admired for their response and bravery. This to me demonstrates how our culture on the whole values brashness and no-holds bar behavior from White males, yet these same behaviors are considered aggressive and undesirable in minorities, especially Black males. According to Zimmerman’s lawyer and friends, he was justified in his pursuit of Trayvon, yet, in their minds, Trayvon was not justified if he had turned and faced his pursuer in the very least, and defended himself at the most. How can both perceptions exist at the same time? It goes back to what we value as appropriate responses from specific subject positions. How is it that the only seemingly acceptable response that Trayvon should have had was to run?

A recent blog by Michael Skolnik points out, if it had been him, rather than Trayvon, he doubts that Zimmerman would have seen him as suspicious. He states:

No matter how much the hoodie covers my face or how baggie my jeans are, I will never look out of place to you. I will never watch a taxi cab pass me by to pick someone else up. I will never witness someone clutch their purse tightly against their body as they walk by me. I won’t have to worry about a police car following me for two miles…I will never look suspicious to you, because of one thing and one think only. The color of my skin. I am white.

The point being, if Trayvon were White, how different would the conversation be? Based on which underlying beliefs and values would the media and others’ respond? How does this notion change the conversation completely?

Reversal of Fortune

The last and most important question that remains unaddressed is if the situation was reversed, would we even have this same degree of speculation? I suspect that had Trayvon been the one to carry a weapon, even with a permit, Trayvon Martin would be held in jail with a hefty bond. The media would ponder why this “troubled teen” went out to kill a law-abiding Neighborhood Watch captain. Not only would the questions surrounding the incident (I doubt anyone would have asked if George Zimmerman was agitated that night) would have been different, but also the language used to frame the incident would likely have included emphasis of murder and killing rather than a death. How do we continue to talk about Trayvon’s death as if his death wasn’t the result of another’s intentional or unintentional actions.

Missing Conclusion

It seems to me if George Zimmerman never spends a night in jail, if the Stand Your Ground law only applies to him and is a means of his escaping criminal liability for his actions, and not to Trayvon who reasonably felt he was defending his own life, then we are saying to everyone that it’s okay to shoot an unarmed 17-year old Black male, as long as you feel threatened. And in doing so, we continue to justify the perpetuation of fear of Black men and boys.

How is this substantially different than our recent and unfortunate racial history?

West Wind Education Policy and Diversity Focus announce a new partnership, The Creative Corridor Center for Equity.

West Wind Education Policy and Diversity Focus announce a new partnership, The Creative Corridor Center for Equity.

Everybody can be great, because anybody can serve.

Everybody can be great, because anybody can serve. As I drove into work this morning, I realized that in a foreseeable amount of time (one month from now), a long-term goal that has been one of the biggest challenges I ever set out to achieve will culminate: I will defend my dissertation and have earned my PhD. Though it’s easy to pat myself on the back for realizing a long-held dream, I think it’s important to acknowledge that I didn’t get here alone.

As I drove into work this morning, I realized that in a foreseeable amount of time (one month from now), a long-term goal that has been one of the biggest challenges I ever set out to achieve will culminate: I will defend my dissertation and have earned my PhD. Though it’s easy to pat myself on the back for realizing a long-held dream, I think it’s important to acknowledge that I didn’t get here alone.  I have easily watched more television since the Olympics began on July 27 than I have since July of last year. It is so easy to just keep watching event after event. The command athletes have over their sports, their bodies, and their minds is evident and addictive to watch and think about. But, the actual competition is only part of the story and only part of what keeps me roped in.

I have easily watched more television since the Olympics began on July 27 than I have since July of last year. It is so easy to just keep watching event after event. The command athletes have over their sports, their bodies, and their minds is evident and addictive to watch and think about. But, the actual competition is only part of the story and only part of what keeps me roped in.  Thank you, Deborah Meier, for being able and willing to reveal your own racism! As Meier tells Diane Ravitch in the

Thank you, Deborah Meier, for being able and willing to reveal your own racism! As Meier tells Diane Ravitch in the  When I first became a teacher, honestly, I didn’t think race mattered. As a child who grew up in single-parent, low-income household, when I first graduated college, I felt I was the “model” of the American Dream. As a homeowner, mother, wife, college graduate, there were many reasons for why I didn’t challenge the paradigm that I was the exception.

When I first became a teacher, honestly, I didn’t think race mattered. As a child who grew up in single-parent, low-income household, when I first graduated college, I felt I was the “model” of the American Dream. As a homeowner, mother, wife, college graduate, there were many reasons for why I didn’t challenge the paradigm that I was the exception.