What Binary?

Everyone looks out their own window.

White and black make up a spectrum that our society resorts to in conversations of race. By today’s standards, this binary is simply not sufficient. My vacation to the Southwest was a harsh reminder of this.

Recently, I returned to the Southwest for a range of reasons. First and foremost, it was a vacation. But by today’s standards, that does not mean I was not busy. As a former AmeriCorps volunteer in San Antonio, Texas; I find it important to not treat my year of service as only a year of service. It has shaped me in immeasurable ways. I was born and raised in Iowa, but have felt strongly rooted and cultivated in Texas.

I was 23 years old when my AmeriCorps placement in 2009 took place at a local community center. My primary responsibility was to interact with youth between the ages of 5-17 in an after school setting. That experience largely inspired me to further my work with youth, hopefully impacting their lives for the better and providing them a role model as fellow children of color.

Yesterday I visited the community center and spent the afternoon and early evening catching up with the youth I had previously worked with. This visit was bittersweet. On the one hand, it was like any other day at the community center, as though I had never left. However, some of what I saw as a visitor reminded me of why I am so grateful to work at West Wind—why working to infuse race and equity into education policies is important.

Having recently moved back to Iowa , I am still experiencing the impact my year in San Antonio has had on me; spiritually, vocationally, etc. I reflect on my own childhood, growing up as one of the only Latina children in my classroom(s). To witness the youth at this community center in quite a reversal of settings (their neighborhood being 98% Mexican), and in relating it to my work thus far at West Wind, I have gained many insights:

- Being the majority, obliviousness to “the other” is almost unconscious.

- The other is either and both invisible and hypervisible at once.

- Being Latino further complicates the self-identification process for all Latinos; including those who are a part of a majority group like the youth I served on the San Antonio Westside.

These youth freely use the n-word. With conviction. To which their peers laugh. This created for me lumps in my stomach and pain in my heart. A third-grader, knowing how to use that word so harshly and not knowing at all the hurt it stemmed from and its persistent consequences is difficult to see.

They mention a student in their class who they make fun of because, “she is brown”.

“But, you’re brown; too,” I retort.

“No miss, I’m white. I’m Mexican.”

In a world where labels are forced upon all of us, but with the complexity of having to be succinct in our self-labeling , we rush to fit ourselves into boxes that can be easily checked. White. Latino. Non-White. Latino/Hispanic, and so on.

I grew up, the rare Latina in my classroom(s), molding into that binary of black or white. (No in between existed, or at least it wasn’t prioritized in conversations on race.) I wanted badly to be positioned with the white majority, but learned that would never happen, no matter how hard I tried because of how I looked. I responded by aligning with my black peers.

These youth grow up, only surrounded by “Mexicanness” in their homes and classroom(s). But they also are unconsciously aware that, “White is right”.

In 2011, narrowing one’s identity down between White and Black is not that simple.

As I experienced while living in San Antonio, most of these youth will be born, raised, rooted and cultivated in their current neighborhoods. They will only encounter other Mexicans and, if a black person is seen walking the sidewalks, he/she would be immediately questioned. If, by chance, one of their classmates is black, that student will struggle to confidently identity as such.

Black, white, brown, Latino/Hispanic or not. The checkmarks we so frequently are asked to make in a hurry, imply a lot more than we realize; more irreversibly than we realize.

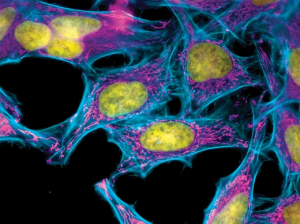

I just read the New York Times best-seller “The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks.” Henrietta Lacks was a black woman treated for cervical cancer at John Hopkins in the early 1950s. It was during this treatment that her cancer cells were taken without her knowledge, grown in a laboratory, and sold to scientists around the globe. Henrietta died in 1951 at the age of 31, but her cells, known to scientists as HeLa, live on in laboratories and medical schools around the globe. HeLa was vital to the development of the polio vaccine, cloning, gene mapping, in vitro fertilization, and much more. In 1996, Roland H. Pattillo, M.D., a professor in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology of Morehouse School of Medicine, began the annual

I just read the New York Times best-seller “The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks.” Henrietta Lacks was a black woman treated for cervical cancer at John Hopkins in the early 1950s. It was during this treatment that her cancer cells were taken without her knowledge, grown in a laboratory, and sold to scientists around the globe. Henrietta died in 1951 at the age of 31, but her cells, known to scientists as HeLa, live on in laboratories and medical schools around the globe. HeLa was vital to the development of the polio vaccine, cloning, gene mapping, in vitro fertilization, and much more. In 1996, Roland H. Pattillo, M.D., a professor in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology of Morehouse School of Medicine, began the annual

On the morning of August 3 the West Wind team joined other volunteers and organizers from To Gather Together, a local organization that gathers donations to buy school supplies from churches, individuals, businesses, and social services agencies. To Gather Together provides school supplies to over 3,000 children in Johnson County, Iowa. West Wind staff assisted by counting out supplies such as crayons, markers, folders, and paper. We sorted the supplies into stacks for specific schools and teams of volunteers delivered these the next day.

On the morning of August 3 the West Wind team joined other volunteers and organizers from To Gather Together, a local organization that gathers donations to buy school supplies from churches, individuals, businesses, and social services agencies. To Gather Together provides school supplies to over 3,000 children in Johnson County, Iowa. West Wind staff assisted by counting out supplies such as crayons, markers, folders, and paper. We sorted the supplies into stacks for specific schools and teams of volunteers delivered these the next day. Last month my mother, Sherry Bozarth, retired from 18 years in the Oklahoma public school system. She took a position in the school cafeteria when I was in junior high so that she would have the same schedule as my sister and I – and, I suspect, so that she could keep an eye on us. After several years, she became a para-professional, a position she held for 13 years. Para-professionals support special educational needs students in the classroom. Over the years she worked with a broad range of students with very different needs. And during that time, as I watched her grow within her career, I learned a lot about what it takes to offer education to all students.

Last month my mother, Sherry Bozarth, retired from 18 years in the Oklahoma public school system. She took a position in the school cafeteria when I was in junior high so that she would have the same schedule as my sister and I – and, I suspect, so that she could keep an eye on us. After several years, she became a para-professional, a position she held for 13 years. Para-professionals support special educational needs students in the classroom. Over the years she worked with a broad range of students with very different needs. And during that time, as I watched her grow within her career, I learned a lot about what it takes to offer education to all students.