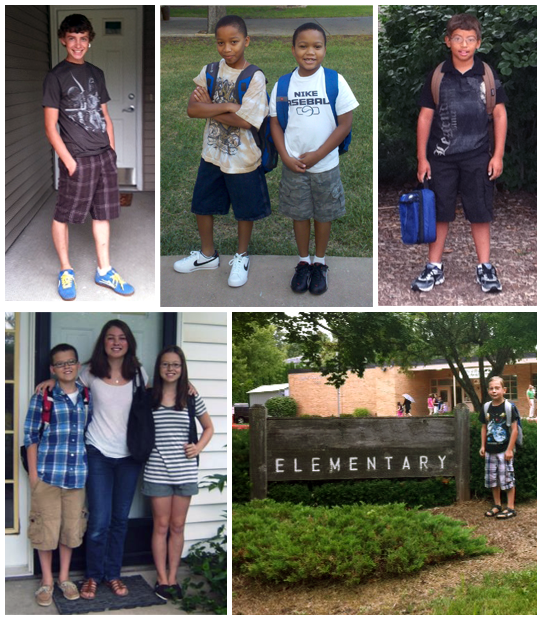

Reading Time: 5 minutes The last day of the 2010-11 academic year for my kids was four days ago. It was a milestone day for both of my kids. My son finished his two years in junior high and is preparing to head into high school. My daughter finished 6th grade, capping off her—and our—elementary school experience. She is preparing to transition to the junior high school that my son is departing.

The last day of the 2010-11 academic year for my kids was four days ago. It was a milestone day for both of my kids. My son finished his two years in junior high and is preparing to head into high school. My daughter finished 6th grade, capping off her—and our—elementary school experience. She is preparing to transition to the junior high school that my son is departing.

As you can imagine, this has been a time of reflection and remembrance for our entire family. Unlike me, both of my kids attended the same school in the same town for their entire elementary school experience. It meant that school was a pretty important institution in both of their lives—and in mine. It also meant that I got to be a part of a particular school community for nine straight years. As we leave that elementary school for good, I thought I would share a few reflections about what mattered to us as a family over these past nine years in one elementary school.

Combined Classes: The elementary school originally was organized with all classes being combined every two years after kindergarten. That meant my son had the same teacher in 1st and 2nd grade, another teacher for 3rd and 4th grade, and another teacher for 5th and 6th grade. Each year, half his class would be new, as the upperclassmen moved on to their next teacher and a new crop of younger students filled in. In 2005, the school decided not to combine 1st and 2nd grade anymore, so my daughter had a different 1st and 2nd grade teacher. But after, she was in the combined classroom experience, too.

The chance for my kids to have teachers who knew them over a long(ish) period of time was valuable. The chance for me and their dad to get to know the teachers over time was valuable. By and large, the teachers really did get to know our kids—and us. We saved a lot of time over the course of those nine years by not having to start over every single year explaining what mattered to us and what we most wanted to work on with our kids.

Not only did the combined classroom model allow for a deeper student-teacher relationship, it also allowed my kids to spend part of their time as the younger kids in a class and part of the time as the older kids. With two children with summer birthdays, this was surprisingly nice. They don’t suffer for being the youngest in their peer group, but it was a nice opportunity to be the older mentors at least part of the time.

Lest you cringe (like I did) at the thought of a kid being stuck with a teacher for two years when the relationship isn’t working out, I do know several students who moved out of a classroom between grades. Admittedly, for some of the parents I know who did this, it was a tough decision to make; it was not common and the ethos was to stay in the assigned classrooms. And it generally required strong parental involvement to make such a choice. But, it was possible, which I thought was pretty important in each case I encountered.

Test data mattered, but SO much mattered more: Yes, we are in Iowa, where standardized testing has been going on for over 70 years. Indeed, we are in Iowa City, birthplace of the Iowa Testing Program and home to ACT and Pearson. In addition to the Iowa Tests of Basic Skills, our school district uses the District Reading Assessment, an interim assessment that gives teachers periodic snapshots of student proficiency. And our teachers were quite adept at being able to use the data from the assessments to decide how to help each student progress. As parents, we were given test score data in our parent-teacher conferences and we discussed with the teachers how they were interpreting the data. I was able to see how data driven decision making made a positive difference in my children’s education.

I also, thankfully, was in a school that did not value test score data over and above other criteria that really mattered. We had a strong principal and thoughtful teachers who did not ostracize us if our kids did not perform well on a test. Admittedly, we were in a privileged position; the school was populated by some pretty privileged kids and was not in danger of being placed on a “watch” list or being bad-mouthed because of the composition and performance of our student body. And it really did take leadership to make sure that test score data had an appropriate place in the educational process.

Which was great, because in the end, I cared so much more about how my kids felt about themselves and about school than I did about how they did on those tests. That’s not say that I wasn’t concerned about their academic performance. I just knew that if they learned in first or second or third grade that they weren’t “smart” or they weren’t valued or they were a problem—or that school was an unfriendly place or that they felt bad being there—then my children really would suffer throughout their school career. I think we made it very clear to all the teachers, principals, and classified professionals what really mattered to us and why. And, they agreed. Almost to the individual teacher, they exhibited care and attention to my children as whole children. Yes, there were a couple of exceptions, but to be in an overall school culture where academics are central but happiness and engagement matter was a good thing.

Race Matters: As I write this, I am reminded of my privileged position, as a white mother with two white children in a predominantly white school system. It took me several years to realize that not all Iowa City schools were created equal and that not all schools had the kind of racial diversity that I had hoped for my kids to be a part of. I know…, “Duh”! We had picked an elementary school not based on test scores or student demographics, but because we found a house we loved and we believed it didn’t matter which elementary school our kids attended. They all were great, we thought, and, given what we did know about the town’ demographics and the reputation of the school, we thought we were in a racially diverse school community. We were wrong.

I realize now that I had a kind of disdain for the practice of picking houses based on the racial make-up and/or the test scores of the neighborhood schools—because too often that has been a way of racially segregating our schools. And so I put on blinders. Looking back, I wish I had looked at the school demographics. It turned out we were on the boundary between two very different elementary schools. I do not want to diminish my children’s feelings of school pride, but I really do wish we had looked for a home just a few blocks to the south so that my kids had attended a much more racially and economically diverse school. I couldn’t see that then, for lots of complicated reasons. But race has mattered a lot in my kids’ school experience. Just because we were in a predominantly racially homogeneous school, doesn’t mean my kids are exempt from race. Quite the opposite! But it is far too easy for us to reflect on our experiences and to forget that being white is to live a racialized existence in the United States today. Thankfully, my kids can reflect openly on their own race and the way race is a factor in our school and our neighborhood. We just too often miss the opportunities to recognize what we are learning and how we are benefiting unfairly by our race.

I hope that by being reflective about my own anecdotal experiences and the experiences my children share with me, I can be somewhat conscious about the perspectives I bring to my work. I hope to constantly work to recognize our perspectives, uncover our blind spots, and acknowledge our biases. Not to deny them, but to better understand them and to build education policies that honor and acknowledge the realities of student and parent experiences and choices.

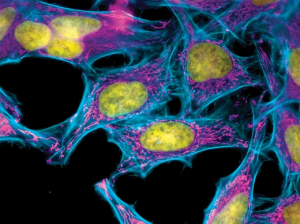

I just read the New York Times best-seller “The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks.” Henrietta Lacks was a black woman treated for cervical cancer at John Hopkins in the early 1950s. It was during this treatment that her cancer cells were taken without her knowledge, grown in a laboratory, and sold to scientists around the globe. Henrietta died in 1951 at the age of 31, but her cells, known to scientists as HeLa, live on in laboratories and medical schools around the globe. HeLa was vital to the development of the polio vaccine, cloning, gene mapping, in vitro fertilization, and much more. In 1996, Roland H. Pattillo, M.D., a professor in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology of Morehouse School of Medicine, began the annual HeLa Women’s Health Conference, and the BBC filmed part of its documentary “The Way of All Flesh” at the event. Yet, before this book, her family was virtually unknown to the general public and could not afford health care that would give them access to the medical advances their own mother made possible.

I just read the New York Times best-seller “The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks.” Henrietta Lacks was a black woman treated for cervical cancer at John Hopkins in the early 1950s. It was during this treatment that her cancer cells were taken without her knowledge, grown in a laboratory, and sold to scientists around the globe. Henrietta died in 1951 at the age of 31, but her cells, known to scientists as HeLa, live on in laboratories and medical schools around the globe. HeLa was vital to the development of the polio vaccine, cloning, gene mapping, in vitro fertilization, and much more. In 1996, Roland H. Pattillo, M.D., a professor in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology of Morehouse School of Medicine, began the annual HeLa Women’s Health Conference, and the BBC filmed part of its documentary “The Way of All Flesh” at the event. Yet, before this book, her family was virtually unknown to the general public and could not afford health care that would give them access to the medical advances their own mother made possible.