Reading Time: 5 minutes People who know me know that I have a healthy National Public Radio (NPR) addiction. As of late, it has become a habit to tune in at work. On Tuesday as I sat at my desk, On Point, a daily opinion call-in show, aired a segment, “Jobless in America” (http://onpoint.wbur.org/2011/08/16/jobless-today-in-america). Two of the guests, both white and unemployed, talked about their experiences with unemployment and their sense of betrayal for “having done everything right,” yet finding themselves unemployed: a situation they never anticipated.

People who know me know that I have a healthy National Public Radio (NPR) addiction. As of late, it has become a habit to tune in at work. On Tuesday as I sat at my desk, On Point, a daily opinion call-in show, aired a segment, “Jobless in America” (http://onpoint.wbur.org/2011/08/16/jobless-today-in-america). Two of the guests, both white and unemployed, talked about their experiences with unemployment and their sense of betrayal for “having done everything right,” yet finding themselves unemployed: a situation they never anticipated.

Although I empathize with those who have lost their jobs during the ongoing recession and are experiencing economic hardships, I must admit that I’m also partially annoyed by the notion that White middle class workers should expect a guaranteed job and a certain lifestyle. As the introduction to the show states:

…There are not enough jobs, by a long shot. It’s crushing individuals and families right now. We’ll hear from some today.

And it’s putting a huge dent in our national future. Changing things we love most about this country.

As I listened to the show and even now as I read these words, what I hear is the collective anxiety and loss of identity that middle class White Americans are experiencing. This is not the first NPR or other media outlet show that has broadcast the woes of our society as being the conundrum of those who ordinarily would expect to never have this problem.

From my position as an African American woman, people of color have historically experienced unemployment and underemployment without questioning whether or not we should believe in the American Dream. In fact my favorite poem, Langston Hughes’, “Harlem” or “A Dream Deferred” (depending on the publication source) as well as the Lorraine Hansberry’s play, “A Raisin in the Sun” speak to the frustrations that people of color, in this case African Americans, have suffered historically when they have tried to assert their right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Rather than the NPR story continuing to promulgate the notion that our current joblessness threatens the fabric of our society, I posit that this is an opportunity to really question the notion of meritocracy.

We live in a society that promotes the idea that as individuals we all have the right and ability to realize our dreams through our own hard work and effort. But when you peel back the layers of that notion, you find that we are a nation of individuals who stand on the shoulders of those who have come before us. David Horwitt (2008) reminds us that every society employs myths in order to explain how those who are privileged are more deserving that those who are not. In his essay, “This Hard-Earned Money Comes Stuffed in Their Genes,” Horwitt discusses the multiple ways in which people gain advantage through no effort of their own. A primary means of unearned gains is inheritance. Though he cites a Forbes article about the wealthiest 400 people who largely inherited their wealth, consider the more typical types of inheritance: a house that is passed down, or jewelry, stocks and bonds, property, vehicles, and so on. These are all units of wealth that lessen the burden upon the individual who now has a commodity simply because the parent left it to the child. Another form of this is a business. Lucrative or not, it is collateral that can be negotiated for personal profit and gain. Other, less obvious advances are college admissions. Many colleges and universities (particularly those top-ranked colleges and university) admit just as many legacy applicants as they do non-legacy applicants. Today, getting into a college or university has become increasingly important. Even with our current downturn, those who have a college education have lower rates of unemployment[1] 5.4% in comparison to 10.3% for those who only have a high school diploma

We live in a society that promotes the idea that as individuals we all have the right and ability to realize our dreams through our own hard work and effort. But when you peel back the layers of that notion, you find that we are a nation of individuals who stand on the shoulders of those who have come before us. David Horwitt (2008) reminds us that every society employs myths in order to explain how those who are privileged are more deserving that those who are not. In his essay, “This Hard-Earned Money Comes Stuffed in Their Genes,” Horwitt discusses the multiple ways in which people gain advantage through no effort of their own. A primary means of unearned gains is inheritance. Though he cites a Forbes article about the wealthiest 400 people who largely inherited their wealth, consider the more typical types of inheritance: a house that is passed down, or jewelry, stocks and bonds, property, vehicles, and so on. These are all units of wealth that lessen the burden upon the individual who now has a commodity simply because the parent left it to the child. Another form of this is a business. Lucrative or not, it is collateral that can be negotiated for personal profit and gain. Other, less obvious advances are college admissions. Many colleges and universities (particularly those top-ranked colleges and university) admit just as many legacy applicants as they do non-legacy applicants. Today, getting into a college or university has become increasingly important. Even with our current downturn, those who have a college education have lower rates of unemployment[1] 5.4% in comparison to 10.3% for those who only have a high school diploma

We are suffering from an unprecedented economic shift. We are no longer alone, but are competing for jobs in a global economy where no one is safe. However, for me the great concern is the jobless rate among people of color. According to the BLS Monthly Labor Review (2011), although the fourth-quarter unemployment rate for Whites fell by .05% to 8.7% it remained in the double digits for African Americans and Hispanics at 15.8% and 12.9%. Prevailing myths may try to convince us that the disproportionate rates among people of color is due to their lack of educational attainment and experience, but as the recent settlement of a 1995 lawsuit against the Chicago firefighter’s entrance exam demonstrates, African American applicants who otherwise qualified[2] were not hired or denied promotions. As a result, the Chicago Fire Department will have to hire 111 firefighters between now and March 2012 as well as pay the remaining 6000 candidates $5000.[3]

A final example is a recent article in Science which investigated the National Institutes of Health reveals that Asians were 4% and African Americans were 13% less likely to win NIH funding. Even when controlled for education, training, previous research rewards and publication record, African Americans were still 10% less likely to receive funding.

These examples represent a need for our society to turn and face ourselves. In order to actually have a meritocracy, we have to be able to guarantee equal access and compensation for equal talent and skill which will require the reformation of policies, procedures, and frameworks that continue to marginalize people of color.

Works Cited

“City to Hire, Pay Back Black Firefighters as Part of Settlement.” Chicago Fox News: Chicago. 17 August 2011. Web. 18 August 2011.

“Education Pays…” The Bureau of Labor & Statistics. 4 May 2011. Web. 18 August 2011. http://www.bls.gov/emp/ep_data_occupational_data.htm

Ginther, Donna K.; Schaffer, Walter T.; Schnell, Joshua ; Masimore, Beth; Liu, Faye; Haak, Laurel L.; Kington, Raynard. “Race, Ethnicity, and NIH Research Rewards. Science 333. 19 August 2011. 1015-1019.

Horwitt, David. “This Hard-Earned Money Comes Stuffed in Their Genes.” Eds. Karen E. Rosenblum & Toni-Michelle C. Travis. 5th Edition. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2008. Print.

“Jobless in America.” On Point. NPR: WBUR, Boston. August 16, 2011. Radio.

Theodossiou, E & Hipple, S. “Unemployment Remains High in 2010” Monthly Labor Review March 2011. Web. August 18, 2011. http://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2011/03/art1full.pdf

Vedantam, Shankar. “In the Boardrooms and in Courtrooms Diversity Makes a Difference.” Washington Post . 17 January 2007. Web. 18 August 2011. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/01/14/AR2007011400720.html

“White Fire Fighters to Share $6M Settlement.” NBCUniversial, Chicago. 11 March 2009 Web. 18 August 2011. http://www.nbcchicago.com/news/local/White-Firefighters-to-Share-6M-Settlement.html

Comic © Gary Varvel (http://blogs.indystar.com/varvelblog/)

[1] For more specific information see the Bureau of Labor & Statistics May 4, 2011 graphic showing that in 2010 those who have less than a college education the unemployment rate was 14.9% compared to 10.3% for high school graduates and 9.2% for those who have some college compared 5.4% for college graduates. The graph includes rates of unemployment up to those who have a doctorate degree as well as gives the median weekly earnings for each of the educational attainment levels from less than high school up to the doctorate level.

[2] According to the Associated Press article (2011), “Before being hired, they must pass the physical abilities test, background check, drug test and medical exam” (online, http://www.myfoxchicago.com/dpp/news/metro/chicago-black-firefighters-lawsuit-settlement-city-hire-pay-candidates-20110817)

[3] It’s interesting to note that in 2009 the same fire department settled a lawsuit in which 75 White firefighters alleged that because the 1986 lieutenants’ exam were “race normed” they suffered from reverse discrimination. They received $6 million to distribute amongst the group of 75, with a separate 100 firefighters receiving “tens of millions” with benefits for the same lawsuit. Even in settling litigation disputes, it seems, those who already had the advantage of gaining employment and moving through the ranks still received more compensation for discrimination which was not as economically and socially impactful. For more information see: http://www.nbcchicago.com/news/local/White-Firefighters-to-Share-6M-Settlement.html. Again the notion of a meritocracy where Whiteness should be rewarded for “doing my part” plays a role in the argument.

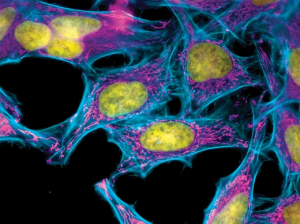

I just read the New York Times best-seller “The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks.” Henrietta Lacks was a black woman treated for cervical cancer at John Hopkins in the early 1950s. It was during this treatment that her cancer cells were taken without her knowledge, grown in a laboratory, and sold to scientists around the globe. Henrietta died in 1951 at the age of 31, but her cells, known to scientists as HeLa, live on in laboratories and medical schools around the globe. HeLa was vital to the development of the polio vaccine, cloning, gene mapping, in vitro fertilization, and much more. In 1996, Roland H. Pattillo, M.D., a professor in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology of Morehouse School of Medicine, began the annual

I just read the New York Times best-seller “The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks.” Henrietta Lacks was a black woman treated for cervical cancer at John Hopkins in the early 1950s. It was during this treatment that her cancer cells were taken without her knowledge, grown in a laboratory, and sold to scientists around the globe. Henrietta died in 1951 at the age of 31, but her cells, known to scientists as HeLa, live on in laboratories and medical schools around the globe. HeLa was vital to the development of the polio vaccine, cloning, gene mapping, in vitro fertilization, and much more. In 1996, Roland H. Pattillo, M.D., a professor in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology of Morehouse School of Medicine, began the annual  People who know me know that I have a healthy National Public Radio (NPR) addiction. As of late, it has become a habit to tune in at work. On Tuesday as I sat at my desk, On Point, a daily opinion call-in show, aired a segment, “Jobless in America” (

People who know me know that I have a healthy National Public Radio (NPR) addiction. As of late, it has become a habit to tune in at work. On Tuesday as I sat at my desk, On Point, a daily opinion call-in show, aired a segment, “Jobless in America” ( We live in a society that promotes the idea that as individuals we all have the right and ability to realize our dreams through our own hard work and effort. But when you peel back the layers of that notion, you find that we are a nation of individuals who stand on the shoulders of those who have come before us. David Horwitt (2008) reminds us that every society employs myths in order to explain how those who are privileged are more deserving that those who are not. In his essay, “This Hard-Earned Money Comes Stuffed in Their Genes,” Horwitt discusses the multiple ways in which people gain advantage through no effort of their own. A primary means of unearned gains is inheritance. Though he cites a Forbes article about the wealthiest 400 people who largely inherited their wealth, consider the more typical types of inheritance: a house that is passed down, or jewelry, stocks and bonds, property, vehicles, and so on. These are all units of wealth that lessen the burden upon the individual who now has a commodity simply because the parent left it to the child. Another form of this is a business. Lucrative or not, it is collateral that can be negotiated for personal profit and gain. Other, less obvious advances are college admissions. Many colleges and universities (particularly those top-ranked colleges and university) admit just as many legacy applicants as they do non-legacy applicants. Today, getting into a college or university has become increasingly important. Even with our current downturn, those who have a college education have lower rates of unemployment

We live in a society that promotes the idea that as individuals we all have the right and ability to realize our dreams through our own hard work and effort. But when you peel back the layers of that notion, you find that we are a nation of individuals who stand on the shoulders of those who have come before us. David Horwitt (2008) reminds us that every society employs myths in order to explain how those who are privileged are more deserving that those who are not. In his essay, “This Hard-Earned Money Comes Stuffed in Their Genes,” Horwitt discusses the multiple ways in which people gain advantage through no effort of their own. A primary means of unearned gains is inheritance. Though he cites a Forbes article about the wealthiest 400 people who largely inherited their wealth, consider the more typical types of inheritance: a house that is passed down, or jewelry, stocks and bonds, property, vehicles, and so on. These are all units of wealth that lessen the burden upon the individual who now has a commodity simply because the parent left it to the child. Another form of this is a business. Lucrative or not, it is collateral that can be negotiated for personal profit and gain. Other, less obvious advances are college admissions. Many colleges and universities (particularly those top-ranked colleges and university) admit just as many legacy applicants as they do non-legacy applicants. Today, getting into a college or university has become increasingly important. Even with our current downturn, those who have a college education have lower rates of unemployment

On the morning of August 3 the West Wind team joined other volunteers and organizers from To Gather Together, a local organization that gathers donations to buy school supplies from churches, individuals, businesses, and social services agencies. To Gather Together provides school supplies to over 3,000 children in Johnson County, Iowa. West Wind staff assisted by counting out supplies such as crayons, markers, folders, and paper. We sorted the supplies into stacks for specific schools and teams of volunteers delivered these the next day.

On the morning of August 3 the West Wind team joined other volunteers and organizers from To Gather Together, a local organization that gathers donations to buy school supplies from churches, individuals, businesses, and social services agencies. To Gather Together provides school supplies to over 3,000 children in Johnson County, Iowa. West Wind staff assisted by counting out supplies such as crayons, markers, folders, and paper. We sorted the supplies into stacks for specific schools and teams of volunteers delivered these the next day. The West Wind Education Policy web site describes our work in the area of knowledge building and professional development as being based on theories of andragogy–or adult learning. The study of adult learning theory and experience in designing and supporting professional development for educators has taught us a lot about the way teachers and school leaders learn when engaging in professional growth experiences. Andragogy theories suggest that adults need to learn experientially and to be actively involved in the planning and evaluation of their instruction. We know that adults learn best when the topic is of immediate value. We know that experience (including mistakes) provides the basis for effective learning activities and that problem-centered learning rather than content-oriented learning is more meaningful to the adult. Educators, like all other adult learners bring with them a reservoir of experiences, but they also bring extensive doubts and fears to the educational process. Well-designed learning establishes an environment where each learner feels safe and supported, where the individual’s needs and uniqueness are honored, and where the participant’s abilities and life achievements are acknowledged and respected. A productive learning environment encourages experimentation and creativity, while fostering intellectual freedom.

The West Wind Education Policy web site describes our work in the area of knowledge building and professional development as being based on theories of andragogy–or adult learning. The study of adult learning theory and experience in designing and supporting professional development for educators has taught us a lot about the way teachers and school leaders learn when engaging in professional growth experiences. Andragogy theories suggest that adults need to learn experientially and to be actively involved in the planning and evaluation of their instruction. We know that adults learn best when the topic is of immediate value. We know that experience (including mistakes) provides the basis for effective learning activities and that problem-centered learning rather than content-oriented learning is more meaningful to the adult. Educators, like all other adult learners bring with them a reservoir of experiences, but they also bring extensive doubts and fears to the educational process. Well-designed learning establishes an environment where each learner feels safe and supported, where the individual’s needs and uniqueness are honored, and where the participant’s abilities and life achievements are acknowledged and respected. A productive learning environment encourages experimentation and creativity, while fostering intellectual freedom.